Jacob Schwartz Scientist & HTML fan

Delta V required for low-TWR take off to orbit around a spherical airless world

$\def\i{\mathrm{i}}\def\twr{\mathcal{T}}\def\vn{V}\def\tn{t_o}\def\d#1#2{\frac{d #1}{d #2}}$Getting to orbit from the surface of a body takes fuel, thrust and time. Using a minimum of delta-$v$ (minimum fuel) is generally reckoned to be the best. In this post, we will present limits on the minimum delta-$v$ to get into orbit, given a rocket with a constant thrust-to-weight ratio $\mathcal{T}$.

A lower orbit takes less delta-v to access. For the lowest orbit possible we will assume the body is perfectly round and has no atmosphere: this orbit will be just skimming the surface. First we will draw a free-body diagram for this problem, then give the equations of motion. Then, in order to give a more universal formula, we will normalize the velocity and time variables to the final orbital parameters. We will solve the differential equation for velocity as a function of time, and then determine the required delta-v to make orbit as a function of $\twr$. A brief discussion and list of future work follows.

Free-body diagram

The equations of motion

Motion is only in the horizontal (orbital) direction. Let $v$ be the velocity of the craft.

\begin{equation} m \d{v}{t} = F_{thrust} \sin \theta \tag{1} \label{eq:h} \end{equation} The vertical force components balance so that the rocket stays at the same height always. \begin{equation} F_{thrust} \cos \theta = m g - m \frac{v^2}{R} \tag{2} \label{eq:v} \end{equation}

$R$ is the radius of the body and $g$ is the surface gravity.

Normalize and eliminate $\theta$

Normalize the velocity to orbital velocity $v_o$: \[ \vn \equiv v/v_o \quad\quad v_o = \sqrt{\frac{\mu}{R}} = \sqrt{g R} \] Here the gravitational parameter is $\mu = g R^2$. Normalize time $t$ to the time to travel one radian of the final, circular orbit $T_0$. \[ \tn \equiv t/T_o \quad\quad T_o = \sqrt{\frac{R^3}{\mu}} \] Normalize the thrust to the weight. \[ \twr = F_{thrust}/mg \] Then equations $(\ref{eq:h})$ and $(\ref{eq:v})$ become \begin{equation} \d{\vn}{\tn} = \twr \sin \theta \end{equation} \begin{equation} \twr \cos \theta = 1 - \vn^2 \end{equation} Eliminating $\theta$, \begin{equation} \tag{3}\label{eq:diffeq} \d{\vn}{\tn} = \sqrt{\twr^2 - (1 - \vn^2)^2} \end{equation} This is an ODE paramaterized by $\twr$.

Solve the differential equation

With the boundary condition that $\vn(0) = 0$, we can solve Equation $(\ref{eq:diffeq})$. Mathematica’s DSolve gives something ugly but it can be cleaned up using the Assumption that $\twr > 1$. The velocity as a function of time is

\begin{equation}

\label{eq:vntn}\tag{4}

\vn(\tn) = - \i \sqrt{\twr -1} \; \mathrm{sn}\left(\i \, \tn \sqrt{1 + \twr} \, \Bigg| \, \frac{1-\twr}{1+\twr}\right)

\end{equation}

Where $\mathrm{sn}$ is the Jacobi elliptic function. Even though there are imaginary $\i$ in the equation, don’t worry, it’s real-valued.

There are several types of Jacobi elliptic function, and we can use an identity to write it without the imaginary symbol:

\[ \mathrm{sn}(u, m) = - \i \, \mathrm{sc}(\i u, 1 - m)\] or \[ - \i \, \mathrm{sn}(\i u, m) = - \mathrm{sc}(- u, 1 - m) = \mathrm{sc}(u, 1-m)\] \begin{equation} \label{eq:vntnsc}\tag{5} \vn(\tn) = \sqrt{\twr -1} \; \mathrm{sc}\left(\tn \sqrt{1 + \twr} \, \Bigg| \, \frac{2\twr}{1+\twr}\right) \end{equation}

Find the delta-v required

Delta-v is the product of thrust and time: $\Delta \vn = \twr \, \Delta t$. In order to compute the $\Delta V$ required, we need to solve for the time required to get to orbit $t_r$. Set $\vn = 1$ and invert $(\ref{eq:vntnsc})$. To invert the Jacobi function, $ a = \mathrm{sc}(b | c) \implies b = \mathrm{sc}^{-1}(a | c)$. \begin{equation} t_r(\twr) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1+\twr}} \; \mathrm{sc}^{-1} \left( \frac{1}{\sqrt{\twr -1}} \,\Bigg|\, \frac{2\twr}{1+\twr}\right) \end{equation} Finally, just multiply the time required by $\twr$ to get $\Delta \vn$. \begin{equation} \label{eq:dvtwr}\tag{6} \Delta \vn(\twr) = \frac{\twr}{\sqrt{1+\twr}} \; \mathrm{sc}^{-1} \left( \frac{1}{\sqrt{\twr -1}} \,\Bigg|\, \frac{2\twr}{1+\twr}\right) \end{equation}

Results

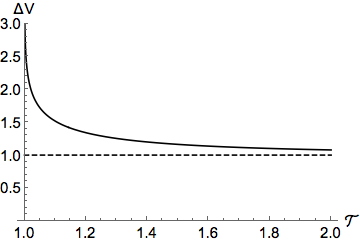

Results are shown in the above plot.

As $\twr \to 1$ the $\Delta \vn$ is infinite, since the rocket can only barely lift off the surface. As $\twr \to \infty$, the maneuver becomes more impulsive and less time is spent pointing the rocket up to balance $mg$.

For a typical $\twr$ of 2, the penalty over an impulsive maneuver is only 8%. For a ‘low’ $\twr = 1.4$, the penalty is 20%. Even for very low $\twr = 1.02$ the required $\Delta \vn$ is only doubled.

Asymptotics

We can find the behavior of the $\Delta V$ for large $\twr$. As $\twr \to \infty$, $\Delta V(\twr) \to 1 + \frac{4}{15}\frac{1}{\twr^2}$.

Discussion

While having a $\twr$ of 2 is a convenient rule of thumb for making orbit, it is not a requirement. Some missions may achieve greater capabilities using a lighter engine with less thrust, if the gains in total $\Delta \vn$ offset the loss due to lower $\twr$.

Future work

- Identify payload ranges and engines that would allow greater capabilites despite a lower $\twr$.

- Extend modelling to include the increase in $\twr$ as fuel is consumed.

- Determine optimal trajectories from the surface to a non-zero-altitude orbit, given constant $\twr$ or $\twr$ as a function of time.