Jacob Schwartz Scientist & HTML fan

Chance of particles passing through a cylinder without interacting

This post is a continuation of the ideas in the previous post.

Motivation

Part of my thesis work involves modeling a cylindrical plasma, and examining what happens when neutral molecules hit it. If the plasma density is low enough, the molecules might pass straight through. If the density is higher, they could be elastically scattered by plasma particles. Or, if the density and temperature are high, they could be ionized. If they are ionized, at what radius does that typically occur? What is the distribution of ionization radii as a function of the incoming particle’s velocities and the mean free time before ionization?

This post solves a related problem.

Problem Statement

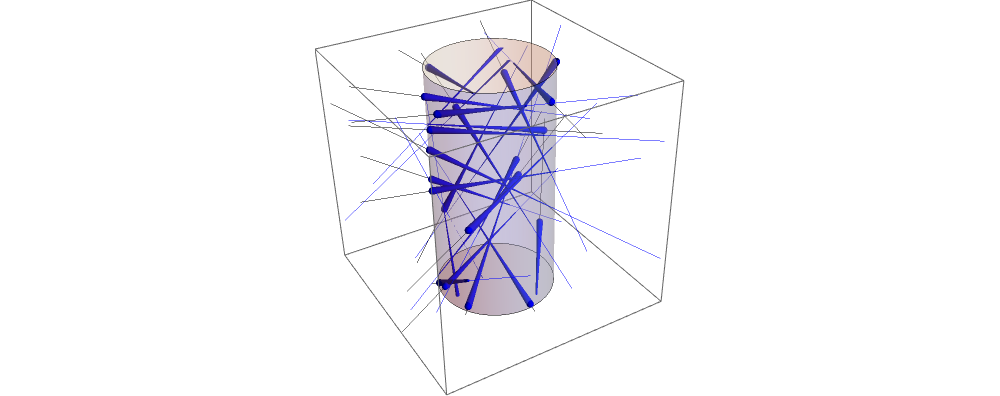

Assume an isotropic bath of non-colliding particles, in which there is a transparent, infinitely long cylinder of radius 1. Particles traveling through the cylinder have a constant chance to interact per unit length $1/\lambda$. You could think of this as an ionization event or a particle decay, although those processes are closer to having a constant probability per unit time. Of the particles that encounter the cylinder, what fraction of them pass through the cylinder without interacting, as a function of $\lambda$?

Solution

A quick simpler problem

First a quick simpler problem for intuition.

Particles move straight toward a wall of thickness 2. When passing through the wall, the have a constant chance to interact per unit length $1/\lambda$. What fraction make it through the wall without interacting?

While at any distance $x$ inside the wall, the chance that the particle has not yet interacted is $\exp(-x/\lambda)$. The chance that a particle passes through without interaction is then $\exp(-2/\lambda)$.

Solving the problem

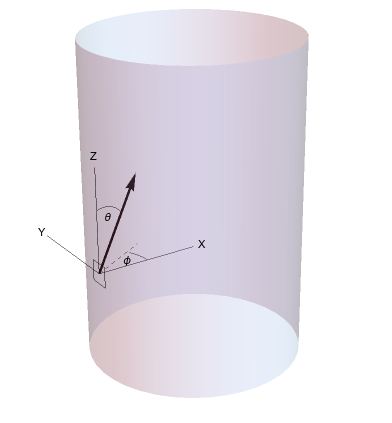

We reuse pieces from the previous post: the coordinate system (shown again in Figure 1), the Lambertian function $l(\theta, \phi) = \frac{1}{4} \sin \theta \cos \phi$ that describes the distribution of particles that hit the cylinder, and the distance function $d(\theta, \phi) = 2 \cos\phi \csc \theta$ which is the length that a particle traveling at some angle would have to spend inside the cylinder.

The integral in the previous post, repeated here in Equation 1, describes the average length that a particle that hits the cylinder travels through it.

\[\begin{equation} \overline{d} = \left< d\right> = \frac{\int_{-\pi/2}^{\pi/2} \int_0^\pi l(\theta,\phi) d(\theta,\phi) \sin(\theta) \; d \theta \; d \phi }{\int_{-\pi/2}^{\pi/2} \int_0^\pi l(\theta,\phi) \sin(\theta) \; d \theta \; d \phi } \tag{1}\label{eq:one} \end{equation}\]Now we want to average the chance that a particle moves through the cylinder without interacting.

The function we need to average over is $\exp(-d(\theta, \phi) / \lambda)$.

We will set up the integral in a similar way:

\[\begin{equation} f(\lambda) = \left<e^{-d/\lambda} \right> = \frac{\int_{0}^{\pi} \int_{-\pi/2}^{\pi/2} l(\theta,\phi) e^{-d(\theta,\phi)/\lambda} \sin\theta \; d \phi \; d \theta }{\int_{0}^{\pi} \int_{-\pi/2}^{\pi/2} l(\theta,\phi) \sin\theta \; d \phi \; d \theta } \tag{2}\label{eq:two} \end{equation}\]We’ve switched the integration order. This turns out to make things easier.

Evaluate

Expanding out the symbols in the numerator and denominator of Equation \eqref{eq:two}, \(\begin{equation} f(\lambda) = \frac{\int_{0}^{\pi} \int_{-\pi/2}^{\pi/2} \frac{1}{4}\sin^2 \theta \cos \phi \; e^{-2 \cos \phi \csc \theta /\lambda} \; d \phi \; d \theta }{\int_{0}^{\pi} \int_{-\pi/2}^{\pi/2} \frac{1}{4}\sin^2 \theta \cos \phi \; d \phi \; d \theta } \tag{3}\label{eq:three} \end{equation}\) The denominator evaluates to $\pi/4$, so we can simplify to \(\begin{equation} f(\lambda) = \frac{1}{\pi} \int_{0}^{\pi} \sin^2 \theta\int_{-\pi/2}^{\pi/2} \cos \phi \; e^{-2 \cos \phi \csc \theta /\lambda} \; d \phi \; d \theta \tag{4}\label{eq:four} \end{equation}\) Focus on the inner integral, \(\begin{equation} \int_{-\pi/2}^{\pi/2} \cos \phi \; e^{-2 \cos \phi \csc \theta /\lambda} \; d \phi \tag{5}\label{eq:inner} \end{equation}\) For now write $\csc \theta / \lambda$ as $a$ \(\begin{equation} \int_{-\pi/2}^{\pi/2} \cos \phi \; e^{-2 a \cos \phi} \; d \phi \tag{6}\label{eq:innera} \end{equation}\) With Mathematica this evaluates to \(\pi (\pmb{L}_{-1}(2 a)-I_1(2 a))\) where $\pmb{L}$ is the modified Struve function and $I$ is the modified Bessel Function of the first kind.

Inserting this into Equation \eqref{eq:four} we have \(\begin{equation} f(\lambda) = \int_{0}^{\pi} \sin^2\theta (\pmb{L}_{-1}(\frac{2}{\lambda \sin\theta})-I_1(\frac{2}{\lambda \sin\theta})) d \theta \tag{6}\label{eq:thetaint} \end{equation}\) Mathematica can’t do this integral … yet.

The transformation!

First do a u-substition $y = \sin \theta$. The integral becomes \(\begin{equation} 2 \int_{0}^{1} \frac{y^2}{\sqrt{1-y^2}} (\pmb{L}_{-1}(\frac{2}{\lambda \; y})-I_1(\frac{2}{\lambda \; y})) \; d y \tag{7}\label{eq:yint1} \end{equation}\) Mathematica still can’t do this integral. Do another u-substitution, $ x = 1/y $. The integral becomes \(\begin{equation} 2 \int_{1}^{\infty} \frac{1}{x^3 \sqrt{x^2 - 1}} (\pmb{L}_{-1}(\frac{2 x}{\lambda})-I_1(\frac{2 x}{\lambda})) \; d x \tag{8}\label{eq:xint1} \end{equation}\) Remarkably, this one Mathematica can do! It evaluates to

\[f(\lambda) = \begin{equation} \frac{1}{3} \left(\frac{8}{\lambda^2}+3 -3 \pi ^{3/2} G_{2,4}^{2,0}\left(\frac{1}{\lambda ^2}\Bigg| \begin{array}{c} 1,2 \\ \frac{1}{2},\frac{3}{2},-\frac{1}{2},1 \\ \end{array} \right)\right) \tag{9}\label{eq:bigG} \end{equation}\]where $G$ is the Meijer G function, a general function defined in such a way that it has some nice properties and relations. More practically, there are stable schemes for its numerical evaluation.

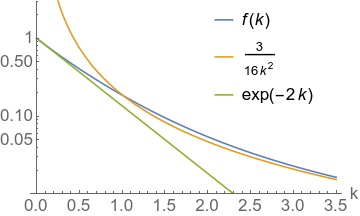

One easy way to plot and compare the function is by defining $k = 1/\lambda$, so that $k$ is the radius of the cylinder expressed in typical reaction lengths.

Figure 2 shows a plot of the $f(k)$ alongside its asymptotics.

Asymptotics

As can be seen readily in the plot, $f(k) \to \exp(-2k)$ as $k \to 0$.

As $k\to\infty$, $f(k) \to \frac{3}{16 k^2}$. Take Equation \eqref{eq:four}:

\(\begin{equation} f(k) = \frac{1}{\pi} \int_{0}^{\pi} \sin^2 \theta\int_{-\pi/2}^{\pi/2} \cos \phi \; e^{-2 k \cos \phi \csc \theta} \; d \phi \; d \theta \tag{4}\label{eq:fouragain} \end{equation}\) For large $k$, the exponential term is very small except where $\cos \phi$ is nearly zero, around $\pm \pi/2$. The integral is symmetric around 0, so for simplity we fold over the $\phi$ integral range in half:

\[\begin{equation} f(k) = \frac{2}{\pi} \int_{0}^{\pi} \sin^2 \theta\int_{0}^{\pi/2} \cos \phi \; e^{-2 k \cos \phi \csc \theta} \; d \phi \; d \theta \tag{10}\label{eq:folded} \end{equation}\]Examining the inner integral, we relabel the angle $\phi’ = \pi/2 - \phi$ to write in terms of $\sin$s.

\(\begin{equation} \int_{0}^{\pi/2} \sin \phi' \; e^{-2 k \sin \phi' \csc \theta} \; d \phi' \tag{11}\label{eq:sinful} \end{equation}\) Since now only $\phi’$ near $0$ matters, we can perform a Taylor expansion of $\sin \phi’$ around $0$, and also formally extend the upper range of the integral to $\infty$. It then evaluates cleanly.

\[\begin{equation} \int_{0}^{\infty} \phi' \; e^{-2 k \phi' \csc \theta} \; d \phi' = \frac{\sin^2\theta}{4 k^2} \tag{12}\label{eq:infinitlysinful} \end{equation}\]Substituing that into the full integral we have,

\[\begin{equation} f(k \to \infty) = \frac{2}{4 \pi k^2} \int_{0}^{\pi} \sin^4\theta \; d \theta = \frac{3}{16 k^2} \tag{13}\label{eq:onlyThetaLeft} \end{equation}\] Written on November 15th, 2018