Jacob Schwartz Scientist & HTML fan

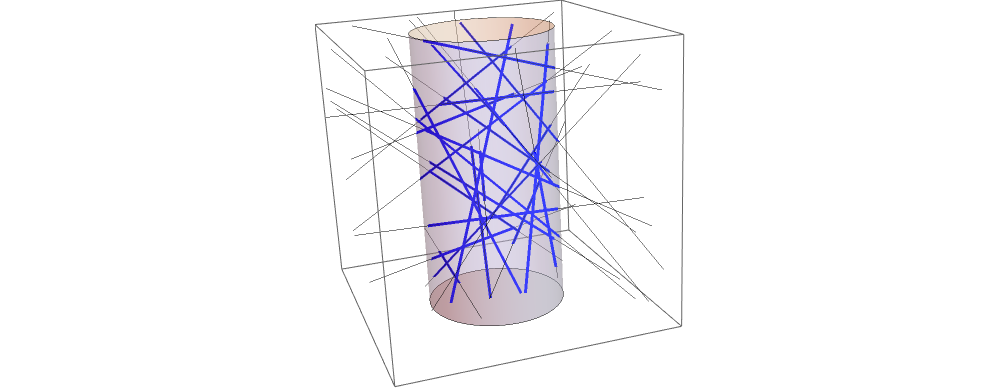

Particles passing through an infinite cylinder

Part of my thesis work involves modeling a cylindrical plasma, and examining what happens when neutral molecules hit it. If the plasma density is low enough, the neutrals might pass straight through. If the density is higher, they could be elastically scattered by plasma particles. Or, if the density and temperature are high, they could be ionized. If they are ionized, at what radius does that typically occur? What is the distribution of ionization radii as a function of the incoming particle’s velocities and the mean free time before ionization?

This post will attempt to lay the groundwork for examining the above issues.

Problem Statement

Assume an isotropic bath of non-colliding particles, in which there is a transparent, infinitely long cylinder of radius 1. Of the particles that encounter the cylinder, on average what distance do they travel through it before exiting?

Solution

The average distance \(\overline{d}\) that particles travel the cylinder is

\[\overline{d} = 2\]Solving the problem

We give two solutions: first, a more complicated calculation in spherical coordinates, and then a simpler one in a hybrid of cartesian and spherical coordinates.

Method 1

Since the cylinder is in an infinite, isotropic bath of particles, every element of area $dA$ on the surface of the cylinder experiences the same particle velocity distribution passing through it.

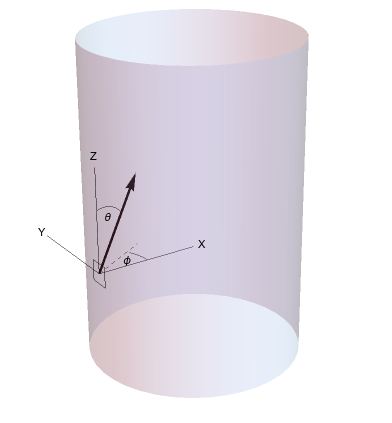

In our calculations, we consider as the origin a point on the surface of the cylinder. See Figure 1. The Z axis is aligned with the cylinder axis. The positive X axis points radially inwards. The azimuthal angle $\phi$ ranges from $-\pi/2$ to $\pi/2$ for angles inside the cylinder, and the altitudinal angle $\theta$ ranges from 0 along the positive Z axis to $\pi$ along the negative Z axis.

Distance $d(\theta, \phi)$

For a given direction $(\theta, \phi)$ we can calculate the distance $d$ that a particle travels through the cylinder. The calculation can be done by multiplying the distance $c$ projected on a circular slice of the cylinder as a function of $\phi$ and an altitudinal enhancement factor $a$ as a function of $\theta$.

First factor, $c(\phi)$

See Figure 2. From elementary trigonometry $c = 2 \cos \phi$.

Second factor, $a(\theta)$.

See Figure 5 in below section ‘Second factor, axial’ for the demonstration that $a = \csc \theta$.

Therefore $d(\theta, \phi) = c(\phi) a(\theta) = 2 \cos \phi \csc \theta$.

Average over particles

This $d(\theta, \phi)$ must be averaged over the distribution of $\theta$ and $\phi$ of particles that encounter the patch of area $dA$ on the surface of the cylinder. For some function x this is \(\begin{equation} \left<x\right> = \frac{\int_{-\pi/2}^{\pi/2} \int_0^\pi f(\theta,\phi) x \sin(\theta) \; d \theta \; d \phi }{\int_{-\pi/2}^{\pi/2} \int_0^\pi f(\theta,\phi) \sin(\theta) \; d \theta \; d \phi } \tag{1}\label{eq:one} \end{equation}\) Applied to $d(\theta, \phi)$ \(\begin{equation} \overline{d} = \left< d\right> = \frac{\int_{-\pi/2}^{\pi/2} \int_0^\pi f(\theta,\phi) d(\theta,\phi) \sin(\theta) \; d \theta \; d \phi }{\int_{-\pi/2}^{\pi/2} \int_0^\pi f(\theta,\phi) \sin(\theta) \; d \theta \; d \phi } \tag{2}\label{eq:two} \end{equation}\)

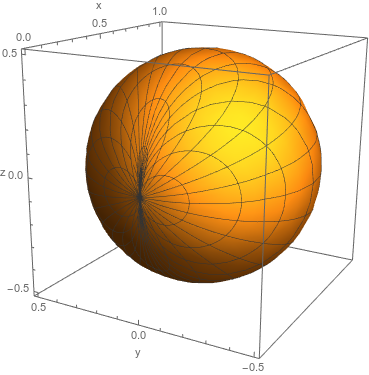

What is $f(\theta, \phi)$?

For an isotropic velocity distribution, the angular distribution of particles that pass through a surface is Lambertian. In our coordinate system, this is represented by \(\begin{equation} f(\theta, \phi) = \frac{1}{4} \sin \theta \cos \phi \tag{3}\label{eq:f} \end{equation}\) It is normalized so that $\int_{-\pi/2}^{\pi/2} \int_0^\pi f(\theta,\phi) \; d\theta \; d\phi = 1$. For a visualization of the Lambertian angular distribution see Figure 3.

Evaluate

Expanding out the symbols in the numerator and denominator of Equation \eqref{eq:two}, \(\begin{equation} \overline{d} = \frac{\int_{-\pi/2}^{\pi/2} \int_0^\pi 2 \cos(\phi)^2 \sin(\theta) \; d \theta \; d \phi } {\int_{-\pi/2}^{\pi/2} \int_0^\pi \cos(\phi) \sin(\theta)^2 \; d \theta \; d \phi } = \frac{2\pi}{\pi} = 2 \tag{4}\label{eq:dbar} \end{equation}\)

Method 2

A second calculation is a bit simpler because it can more easily be broken up into factors.

\[\overline{d} = \frac{\pi}{2} * \frac{4}{\pi} = 2\]The first factor is the average distance the particles travel through the cylinder, perpendicular to the axis. The second factor is the average distance multiplier due to particles’ velocity along the axis.

First factor, perpendicular to the axis

See Figure 4. A particle encountering the disc does so with a particular impact parameter $b$. We want to find $\overline{h}$, the average distance that the particle goes through the disc.

Since the particle bath is uniform and isotropic, the distribution of $b$ is uniform between -1 and 1. Find $h$ as a function of $b$: using the formula for a circle in cartesian coordinates, $h = 2 \sqrt{1 - b^2}$. Taking the average over $h$ over all the $b$:

\[\overline{h} = \frac{\int_{-1}^1 2\sqrt{1- b^2} \; db}{\int_{-1}^{1} \;db} = \frac{\pi}{2}\]The average distance is just the area of the disc divided by the diameter.

Second factor, axial

If a particle has a velocity along the axis it will travel an extra distance in that direction. We need to find the distribution of axial velocities among particles that hit the cylinder. We have assumed an isotropic velocity distribution; \(f(\theta, \phi) = \frac{1}{4 \pi} \sin\theta\).

Particles that will encounter the cylinder do so proportional to their velocity perpendicular to it, so the distribution of particles that hit the cylinder has an extra factor of $\sin\theta$.

\[f_\text{hit}(\theta) \propto \sin^2 \theta\]

See Figure 5. The $d$ for a particle moving through the cylinder at an angle $\theta$ is multiplied by $1/\sin\theta$ compared to if it had $\theta = \pi/2$.

So, the average axial factor is

\[\overline{a} = \frac{\int_{0}^\pi \frac{1}{\sin\theta} \sin^2 \theta \; d \theta}{\int_0^\pi \sin^2 \theta \; d \theta} = \frac{4}{\pi}\]The solution is the product of the perpendicular distance and axial factor:

\[ \overline{d} = \overline{h} * \overline{a} = \frac{\pi}{2} \frac{4}{\pi} = 2 \tag{5} \]

Written on September 30th, 2018